Last week, crowd favourite DSP BlackRock Microcap, a small-cap equity fund stopped accepting fresh investments altogether. This comes a few months after the fund restricted lump-sum investments. Midcap fund Mirae Asset Emerging Bluechip also recently restricted new investments. SBI Small & Midcap and IDFC Premier Equity have had long-standing inflow restrictions.

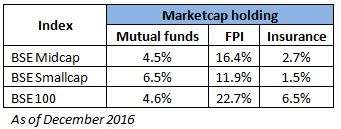

This, when market mavens moan about the lack of penetration of mutual fund investments in the Indian market, with mutual funds holding a dismal 4.5% share of the equity market; and when every expert champions mutual fund as the best product for retail investors. When every fund house, as a business objective, aims for higher AUM, and when investors are willingly investing to build wealth, shouldn’t it be a good thing for everyone concerned? Why should fund houses place restrictions on incoming money then?

The answer lies in the impact mutual funds have on the stocks they hold, and the manner in which inflows come.

Stocks rocket

First, some background. The funds worried about inflows are all concentrated in mid-cap and small-cap funds. The BSE 100, the representative index for large-cap stocks, besides bellwethers Sensex and Nifty had regained their 2008 peak by the end of 2013. The relevant indices for mid-caps and small-caps, the BSE Midcap and BSE Smallcap index were 32% and 51% below their 2008 peaks. In the euphoria generated by the elections in 2014, the entire market took a turn upwards.

First, some background. The funds worried about inflows are all concentrated in mid-cap and small-cap funds. The BSE 100, the representative index for large-cap stocks, besides bellwethers Sensex and Nifty had regained their 2008 peak by the end of 2013. The relevant indices for mid-caps and small-caps, the BSE Midcap and BSE Smallcap index were 32% and 51% below their 2008 peaks. In the euphoria generated by the elections in 2014, the entire market took a turn upwards.

Three factors worked in favour of mid-caps and small-caps more than large-caps – one, they were cheap, having been beaten down so hard, two, the space sported several niche companies that weren’t present in large-caps, and three, in the event of a recovery, smaller companies would grow faster than the larger ones. Lower interest rates would also benefit smaller sized companies more than larger ones.

From late 2013, mid-caps and small-caps marched ever higher, shrugging off the concerns over global upheavals and the slow pace of earnings and revenue recovery in our own markets. The same factors, however, stymied large-cap stocks from mid-2015 until March 2016 and again over the past few months. One reason for this is FPIs – major players in the large-cap space – taking the sluggish earnings cues more seriously. The two BSE indices doubled since the close of 2013; the BSE Midcap index is now 37% above its 2008 peak and the BSE Smallcap index is at that level. Four in ten stocks in this universe doubled.

How does that relate to funds? When investors put in money, their natural tendency is to choose funds that are at the top of the charts at that point. 2014 and onwards were good years where retail investors stepped up their investments in equity mutual funds. This combination resulted in money flowing towards mid-and-small cap funds, especially during mid-2015 to 2016 when large-cap funds corrected in the wake of global uncertainty.

This means that funds are quickly getting a lot of money. This money needs to be invested, and the fund manager cannot hold it as cash. This is where the first reason to curb inflows comes in.

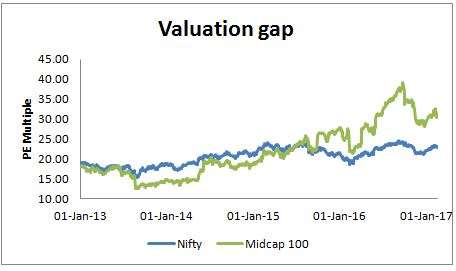

Finding stocks is getting harder. Fund managers in the initial part of the rally had a large, untapped, cheap universe of stocks. That is not so today. Many of the quality mid-cap and small-cap stocks have already been discovered. Mid-cap and small-cap stocks are getting increasingly expensive, pricing in strong earnings and revenue growth. The BSE Mid-cap index’s price-earnings multiple is 29 times while the BSE Smallcap index is at 64 times trailing 12-month earnings. Close to a third of the stocks in these two indices have seen their PE multiples more than double.

Fund managers would thus have to compromise either on quality or valuations or both. Besides, the mid-cap and small-cap space is rife with all manners of companies and little available information to work with. Every new investment that a mid or small-cap fund receives has to be deployed – holding it in cash will hit returns directly, compromising the existing investors of the fund. With stock choices narrowing, some fund managers would rather see fund inflows more controlled so that they have ample time to slowly buy into and identify new stocks.

Fund buying and selling impact stock prices. That’s the second reason causing jitters. In mid-cap and small-cap stocks, funds buying or selling influences stock prices. These stocks do not have much volumes being traded as they are smaller. They have higher promoter holding, leaving fewer shares in public hands. The BSE 100 index has 53% of its market cap held by the public (FPIs, MFs, insurance companies, retail investors, etc) or free-float market cap. In contrast, the BSE Midcap and Small cap indices have 43% and 45% as free-float market cap. A higher free-float market cap allows higher trading. Average volume traded for BSE 100 stocks is around double that of the BSE Midcap or BSE Smallcap stocks.

A fund, as it buys and sells in crores, becomes a huge player in small stocks; MF buying can quickly send a price higher as there’s more demand for stocks and a small supply. The reverse is more alarming – a fund trying to sell a stock can see difficulty in finding counterparties and this pushes prices lower. Selling at lower and lower prices hits fund returns. Consider SRF, among the top holdings in terms of value for mid-cap funds. The daily volumes traded numbers in a few thousands. Mutual funds together hold 56 lakh shares. If these funds try to liquidate their holdings in the share, they aren’t going be able to do it easily or quickly.

Further, in small-sized stocks, institutional holding is low. It’s these institutions that can match fund volume requirements. In the BSE 100 index, 34% is held by institutions (see table). The BSE Midcap index is much lower at a 24% institutional holding and the BSE Smallcap index is even lower at 20%.

Further, in small-sized stocks, institutional holding is low. It’s these institutions that can match fund volume requirements. In the BSE 100 index, 34% is held by institutions (see table). The BSE Midcap index is much lower at a 24% institutional holding and the BSE Smallcap index is even lower at 20%.

There are mid-cap funds that are still managing the show. This does not mean it is easier for them than other mid-cap funds. They manage, either because their asset size or inflow is not grossly out of proportion yet, or they have moved to slightly larger stocks that provide liquidity. Funds such as HDFC Mid Cap Opportunities and Franklin India Prima are cases in point.

A market correction makes the liquidity issue worse. Remember that mid-cap and small-cap stocks can crash just as much as they soar – it took them five years to recover from their 2008 crash. Mid-cap and small-cap stocks may well be ripe for a correction as the valuation gap between the Nifty Midcap 100 and the Nifty 100 is widening.

If there is any sort of correction here, it can be steep and this can cause investors to race for the exit. To meet these redemption demands, funds may have to sell its stocks. Such liquidation can be hard during a correction to begin with, more so when there is little liquidity. The impact on stock prices and returns can be exacerbated.

In a nutshell, funds are finding it increasingly hard to identify and invest in stocks that are fundamentally sound, reasonably valued, and reasonably liquid. In such a situation, fund manager tries to protect the returns of existing investors and still deliver decent performance by limiting the amount of money they take into the fund.

If you hold funds that have stopped fresh inflows, it is not a sign for you to exit the fund. Continue to hold your investments. If such funds form a significant chunk of your holdings, make additional investments in other categories.